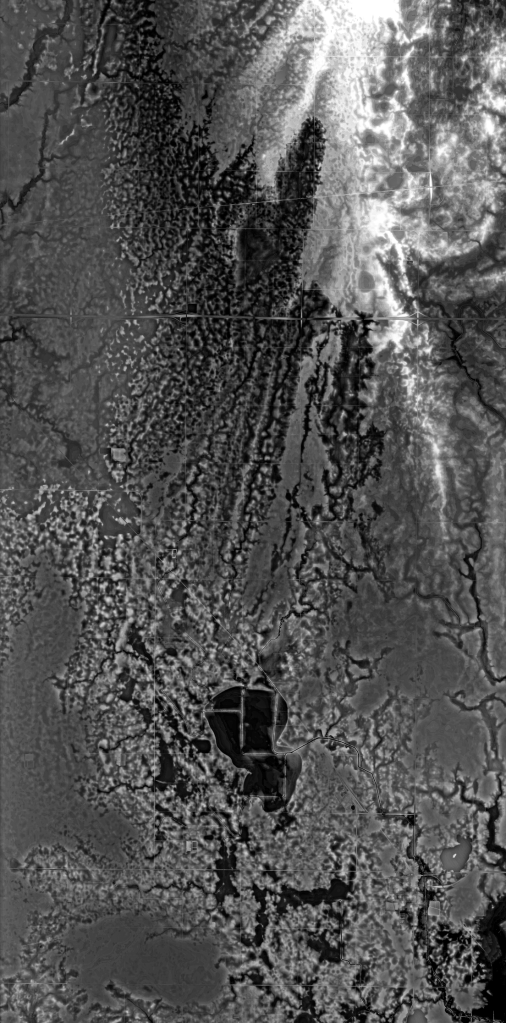

REMs on aluminum composite, 2024

Twelve-thousand years ago, north-central Iowa was the epitome of drama. During the Wisconsin glaciation phase of North America, the great ice behemoths of the Des Moines Lobe inched across the landscape, pulverizing everything into flat, glacial terrain filled with wetland prairie. A sea of grasses connected these islands of water, lakes and potholes, into a subtle but intricate ecosystem.1 Today, the former wetland prairie of north-central Iowa is the most ecologically altered place in North America.2

European settlers drained this place starting in the late-1800s. Farmers plowed under the native flora, excavated the soil, and installed miles of underground drainage tile.3 With farmland consolidation in the mid-1900s and later, the infrastructure became ever-more sophisticated. These farm fields are built environments, though they might not look that way to the untrained eye. This ‘quintessential American heartland’ is cultivated by machines–a product of human artifice through complex, designed systems of infrastructure valued as some of the highest quality agricultural land in the world.

Just twenty-six miles north of where you are standing, a former lake, Lake Cairo, existed.4 In 1895, D. A. Kent, a former professor at the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (known as Iowa State University today), attempted to drain Lake Cairo, seeking to better exploit the high quality soil of the lakebed. Kent’s experiment failed financially in 1897, leaving Hamilton County to finish the drainage process. By 1911, Lake Cairo no longer existed as a lake; its disappearance makes it a typical example of a large-scale pattern in the region.

This overwhelming process of change is an example of slow violence. Slow violence is not explosive. It is unspectacular. It occurs gradually and out of sight. It doesn’t “erupt into instant sensational visibility.”5 It is ignored with the consequences not felt or realized for decades or centuries; a “delayed destruction across space and time.”6 Much of the slow violence carried out within Iowa is out-of-sight to those who do not live in the state, but to the people who live there, it is also out-of-sight. What happened to Lake Cairo was not a rare, single occurrence. Of the 26,545,960 acres of cropland in Iowa, 59.5% is drained.7

These visualizations aim to digitally reconstruct the historical ecologies of the Lake Cairo watershed, known as Drainage District No. 71. By blending organic and linear shapes, they reveal the interplay between the natural ecosystem and human-made infrastructure. The process involves using bare-earth LiDAR digital elevation models (DEMs or digital terrain models, DTMs), which are converted to relative elevation models (REMs) in QGIS. These REMs make it easier to visualize the watershed’s transformation over time, changes that are often hidden due to the landscape’s drastic alteration into farm fields. Through these visualizations, the story of Lake Cairo and its watershed is brought to life in a way that can no longer be seen on the ground.8

References:

1) The prairie pothole region covered 3.25% of the landmass of the North American continent across six states, three provinces, and the territories of, at least, twenty-nine Indigenous groups.

2) Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine; Merchant J, Coussens C, Gilbert D, editors. Rebuilding the Unity of Health and the Environment in Rural America: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006. 3, The Role of the Natural Environment in Rural America, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56969/.

3) Christopher S. Jones, Jacob K. Nielsen, Keith E. Schilling, and Larry J. Weber, “Iowa Stream Nitrate and the Gulf of Mexico,” in PLOS ONE 13, 4 (April 12, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195930.

4) “Hamilton County Has Only One Lake,” Webster City Daily News, August 18, 1921.

5) Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 2-3.

6) Nixon, p. 2-3.; Matthew R. Sanderson and Stan Cox, “Big Agriculture Is Leading to Ecological Collapse,” Foreign Policy, The Slate Group (May 17, 2021). https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/17/big-industrialized-agriculture-climate-change-%20earth-systems-ecological-collapse-policy/.

7) “State Summary Highlights: 2017,” 2017 Census of Agriculture – State Data (U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017).; “Land Use Practices: 2017 and 2012,” 2017 Census of Agriculture – State Data (U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017), https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_2_US_State_Level/.

8) This work adapts a method developed by Dan Coe of the Washington Geological Survey, https://dancoecarto.com/work.